A Concert of Powers for the 21st Century

Toward a more stable and balanced international order rooted in major power coexistence.

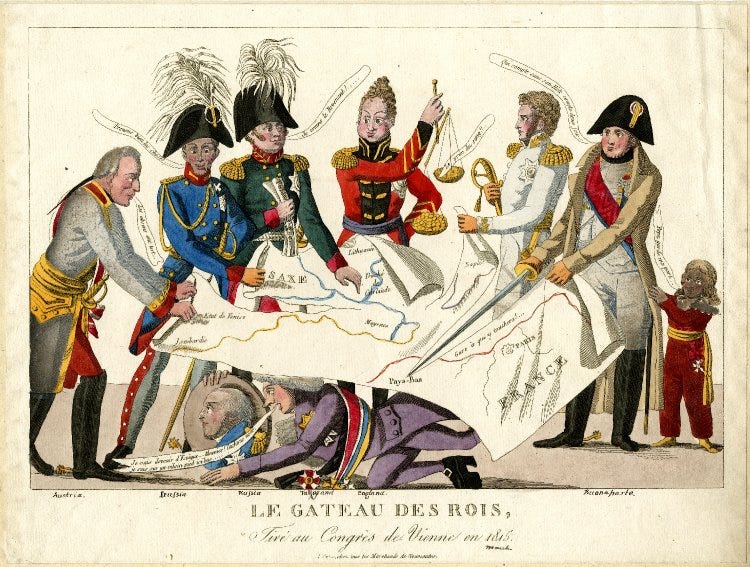

Abstract: The 19th century’s Concert of Europe, an informal agreement amongst victors of the Napoleonic Wars, offers valuable insights for a potential future global order. This article examines the Concert's successes and shortcomings, exploring the potential for a 21st-century “Concert of Powers” adapted to address contemporary challenges unleashed by the unraveling of the postwar order.

Introduction

The tumultuous 19th century witnessed a period of relative peace under the diplomatic framework created by the Concert of Europe. This informal pact, forged by the victors of the Napoleonic Wars, aimed to maintain a balance of power and prevent further large-scale conflict. While not without limitations, the Concert offers valuable lessons for a world grappling with new global challenges. This article examines the Concert of Europe, its successes and shortcomings, and explores the potential for a revitalized global order through a 21st-century “Concert of Powers” adapted to the polycentric realities of our time.

The Concert of Europe: Order Through a Precarious Balance

Following Napoleon Bonaparte’s final defeat in 1815, the victors of the Napoleonic Wars convened in Vienna. This grand gathering, known as the Congress of Vienna, aimed to reshape Europe’s shattered political landscape and prevent the continent from descending back into the chaos that had marked the previous decades. The outcome of this congress wasn't a formal treaty but a tacit understanding — the Concert of Europe.

This Concert lacked the rigidity of a traditional alliance system. It functioned more like a club of the great powers — Austria, Prussia, Russia, Great Britain, and a cautiously reintegrated France. The glue that held this club together was not a formal document but a shared interest: preserving the territorial and political status quo established at Vienna. The resulting balance of power wasn’t static. The Concert envisioned a dynamic system where the great powers actively monitored and adjusted the distribution of power to prevent any single nation from achieving a dominant position that could threaten the peace of Europe.

The Concert of Europe relied on two foundational principles to maintain this delicate balance. The first was the concept of legitimacy. The upheavals of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars had overthrown many hereditary monarchies. The Concert championed the restoration of these dynasties, viewing them as pillars of stability and a bulwark against the spread of revolutionary ideals. This principle, however, proved to be a double-edged sword. Not only did it justify intervention against revolutionary movements, but it also contained the seeds of future tensions as the rise of new ideologies — namely nationalism and liberalism — challenged the legitimacy of the restored order.

The second pillar of the Concert was the principle of collective security. Here, the great powers agreed to intervene — both diplomatically and, if necessary, militarily — to suppress revolutionary movements and uprisings that threatened to upset the established order. This collective security mechanism aimed to prevent localized conflicts and civil wars from escalating into wider European wars. However, the question of which uprisings constituted a legitimate threat and which were simply expressions of national aspirations remained a point of contention within the Concert, leading to inconsistencies in its application.

The Concert of Europe relied on two foundational principles to maintain this delicate balance. The first was the concept of legitimacy; the second, the principle of collective security.

In essence, the Concert of Europe was a complex and sometimes contradictory system. It sought to maintain stability through a balance of power, but this balance was inherently precarious. Its emphasis on (traditional) legitimacy clashed with the rising tide of nationalism, and its application of collective security lacked clear guidelines. Despite its limitations, however, the Concert ushered in a period of relative peace in Europe for several decades — a testament to the effectiveness of a shared interest in maintaining a stable order, even if the methods employed were not always without their drawbacks.

The Concert’s Legacy: A Balancing Act Between Order and Change

The Concert of Europe’s early decades provided a semblance of peace on the continent. While conflicts on the continent did not completely disappear, there was a significant decrease in the scale and frequency of warfare compared to the preceding Napoleonic era. The Concert’s success in quelling revolutionary uprisings in Italy and Spain, such as the Carbonari revolts in the 1820s, underscored the European powers’ strong commitment to collective action. Their swift intervention through diplomatic pressure and, in some cases, military force, effectively stamped out these challenges to the established order.

Nevertheless, as the 19th century progressed, cracks began to appear in the facade of stability. The Concert's legitimacy-based approach, heavily invested in restoring hereditary monarchies, increasingly clashed with the rising tide of nationalism and liberalism. These ideologies — emphasizing national self-determination, popular sovereignty, and individual freedoms — fundamentally challenged the core tenets of the Vienna settlement, which had imposed a political map that often disregarded popular aspirations.

The revolutions of 1848 across Europe served as a stark wake-up call for the Concert. Revolutionary fervor swept across the continent, from France to the German Confederation, threatening to topple the very order the Concert had aimed to preserve. Faced with this unprecedented wave of unrest, the great powers were forced to prioritize stability over strict adherence to the principle of legitimacy. While they initially intervened to suppress these uprisings, the sheer scale and intensity of the revolutionary fervor became undeniable. In such a context, a rigid insistence on the status quo could have plunged Europe back into widespread conflict.

The Concert’s growing pragmatism and prioritization of realpolitik were key factors in its longevity.

This critical juncture revealed the crucial element of adaptability within the Concert. While initially steadfast in suppressing nationalist movements, the Concert ultimately recognized the futility of resisting powerful historical forces. In the case of Italian and German unification, the great powers displayed a degree of pragmatism by facilitating these unifications and even countenancing territorial swaps, such as with the Plombières Agreement in 1858, albeit with certain conditions attached. This shift in approach highlighted the importance of the Concert's second foundational principle — a sound understanding of the balance of power. As the distribution of power in Europe shifted, marked by Prussia’s rise and Austria’s relative decline, the Concert adapted its strategy to maintain a semblance of equilibrium. This adaptability, even if motivated by realpolitik considerations, proved to be a key factor in the Concert’s relative longevity.

Ultimately, the Concert’s legacy remains a mixed one. It ushered in a period of relative peace in Europe, but this stability came at the cost of suppressing popular movements for change. Yet, as the limitations of its legitimacy-based approach became evident, the Concert’s adaptability and understanding of the balance of power allowed it to navigate a complex period in European history.

Building a 21st Century Concert of Powers

The legacy of the Concert of Europe offers valuable insights into constructing a sustainable global order for the 21st century. The first lesson lies in the necessity of grounding such an arrangement in today’s global distribution of power. Only major powers, with significant economic and military capabilities, can provide the leadership and resources needed to maintain a global balance. However, defining “great powers” in the 21st century requires a more nuanced understanding.

Unlike the relatively homogenous Europe of the 19th century, today’s global stage features a heterogeneous array of powerful states. Rising civilizational powers such as China and India challenge the traditional dominance of the West, while regionally focused middle powers — including Turkey, Brazil, and South Africa — play increasingly influential roles.

Where the original Concert of Europe focused primarily on stabilizing a post-revolutionary Europe ravaged by continental war, the new Concert of Powers would be concerned with creating and sustaining a post-unipolar global order to prevent great power war.

Beyond recognizing the shifting balance of power, a successful 21st-century Concert of Powers would require shared, “value-neutral” norms to advance its overarching goals. In a world lacking a hegemon, the core objective of preserving peace and stability would undoubtedly remain paramount. However, the emphasis must shift from the 19th century’s focus on maintaining the status quo to a more adaptive and multifaceted approach.

This new approach would prioritize mechanisms for peaceful conflict resolution. Recentering diplomacy and developing robust systems for mediation, arbitration, and conflict prevention would be crucial to defusing disputes before they escalate into violence.

The Concert would also need to grapple with the fundamental challenge of managing a multipolar, multi-civilizational order. Where the original Concert of Europe focused primarily on stabilizing a post-revolutionary Europe ravaged by continental war, the new Concert of Powers would be concerned with creating and sustaining a post-unipolar global order to prevent great power war.

The UN Security Council is poorly placed to serve as the institutional manifestation of a new Concert of Powers. A product of the post–World War II liberal international order, the Security Council lacks the agility and the legitimacy of the historical Concert of Europe.

Procedural norms are equally important. The Concert of Europe, with its reliance on informal conferences, demonstrated the value of agile diplomacy. Regular communication and a commitment to finding consensus through open dialogue would be essential for a 21st-century Concert. Moreover, the Concert’s history also shows the importance of restraint: intervention should be a last resort, employed only when diplomatic efforts fail and the Concert decides unanimously to defend the global equilibrium from a truculent power seeking global hegemony.

Notably, the UN Security Council, as currently constituted, is poorly placed to serve as the institutional manifestation of a new Concert of Powers. A product of the post–World War II liberal international order, the Security Council lacks the agility and, increasingly, the legitimacy of the historical Concert of Europe. Its cumbersome, legalistic structure and exclusionary nature —limiting its permanent members to the so-called victors of World War Two— is ill-suited to the rapidly evolving realities of a polycentric world.

A new Concert of Powers would require a more informal arrangement combined with a more flexible institutional framework — one that allows for the inclusion of emerging powers and fosters a more dynamic process of consultation and decision-making. The success of this new Concert would hinge on the ability of the system’s superior powers — the U.S., China, India, France, Turkey, Japan, Iran, and Russia — to find common ground on a core set of principles. These principles could include respect for territorial integrity, domestic non-interference, the peaceful resolution of disputes, and collective action on global challenges and opportunities.

Challenges and Opportunities: A Concert for Our Times

The original Concert of Europe was built on two pressing concerns: preventing the devastation of another large-scale war and suppressing the revolutionary movements that had led to the chaos of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars. Any effort to create a 21st-century Concert of Powers must similarly rest on a shared sense of urgency in the face of intensifying global threats.

Addressing Pressing Global Concerns

The agenda of a modern Concert would extend beyond managing historical rivalries to confronting the most urgent challenges of our multiplex world. Preventing interstate war remains a foundational goal — even if total war between major powers appears less imminent. The Concert could serve as a platform for preventive diplomacy, mediating disputes before they escalate. It could also help institutionalize arms control norms and confidence-building measures to reduce tensions and prevent accidental escalation.

Among today’s most destabilizing threats is the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. From North Korea’s nuclear brinkmanship to Iran’s ambiguous ambitions, WMD proliferation risks eroding already fragile regional balances. A 21st-century Concert could reinvigorate coordination among major powers to enforce nonproliferation regimes and establish collective red lines — not through unilateralism or ad hoc coalitions, but through sustained dialogue and strategic empathy. On the flip side, the development and deployment of environmentally-friendly, civilian nuclear technologies could be a key area for global cooperation among Concert powers.

Unlike the relatively cohesive 19th-century Europe, the current international system is polycentric, encompassing states with diverging priorities, worldviews, and civilizational identities …ensuring all major powers feel represented and heard is vital to the Concert’s legitimacy and efficacy.

Another looming security concern is water scarcity. Exacerbated by global dependence on large-scale industrial agriculture and an overreliance on fossil fuels and dams, the politics of water is increasingly linked to instability and conflict. As climate stress and droughts intensify, competition over transboundary water sources — from the Nile Basin to the Indus River — threatens regional cohesion and heightens geopolitical risk. The Concert could act as a forum for developing shared water governance frameworks and conflict-prevention mechanisms, particularly in vulnerable regions. Here, pooling resources and expertise could accelerate research and development timelines, potentially saving countless lives.

Finally, establishing rapid response mechanisms to deploy medical supplies, personnel, and logistical capabilities to affected regions during future pandemics would require a dedicated emergency response force, ready for rapid deployment.

Impediments to a Concert of Powers

The path to a new Concert is fraught with obstacles. Chief among them is the persistent mistrust between great powers. Historical grievances, ideological divergences, and competition for strategic advantage all contribute to a climate of suspicion. Overcoming this will require sustained dialogue and a willingness to define overlapping interests.

A second impediment is the global resurgence of nationalism and populism. Leaders who emphasize national sovereignty above all may either discount the regional, spatial, and civilizational character of the new global system to advance a narrow nationalism or define their sphere of interest in globalist, maximalistic terms. Myopia, presentism, and overconfidence fueled by domestic political pressures can also dull imagination and make it difficult to commit to long-term strategic frameworks, particularly when electorates demand short-term results.

Third, the diffusion of power in today’s world presents an intrinsic challenge. Unlike the relatively cohesive 19th-century Europe, the current international system is polycentric, encompassing states with diverging priorities, worldviews, and civilizational identities. Achieving consensus in such a diverse environment will be more difficult — but ensuring all major powers feel represented and heard is vital to the Concert’s legitimacy and efficacy.

Unlike rigid Cold War alliances, a 21st-century Concert must be adaptive and adopt an interest-based approach — calibrating responses based on context and avoiding ideological postures.

Despite these challenges, the potential benefits remain compelling. By fostering open dialogue, promoting peaceful coexistence and value-neutral norms, and enabling coordinated action on systemic threats, a Concert of Powers could help build a more stable and resilient world order — particularly by constraining the ambitions of revisionist great powers.

Taming Revisionism: A Concert for a Stable Order

The existing postwar international order faces mounting pressure from revisionist powers such as Russia and China, which seek to reshape global norms and reestablish their spheres of influence. A 21st-century Concert could offer a framework for moderating these ambitions through a mix of diplomatic engagement, deterrence, and strategic empathy.

At its core, the Concert would reaffirm collective security. Presenting a united front against unilateral aggression could deter revisionist behavior. If states know that attempts to redraw borders by force will trigger a concerted response, the risk calculus shifts.

In parallel, the Concert could offer inclusion as an incentive. Granting revisionist states a legitimate stake in shaping the rules of the game could reduce their incentive to act outside them. Engagement need not mean acquiescence, but participation in rule-making can temper confrontation.

The Concert also has a role in addressing the root causes of revisionism. Revisionist rhetoric often taps into real grievances, such as historical injustices or economic inequalities. The Concert could serve as a forum for open dialogue and a fair deliberation of these legitimate concerns. By fostering a spirit of change and common understanding, the Concert could blunt the appeal of revisionist narratives in the post-unipolar era.

Flexibility and pragmatism remain critical. Unlike rigid Cold War alliances, a 21st-century Concert must be adaptive and adopt an interest-based approach — calibrating responses based on context and avoiding ideological postures. Such agility would enhance both credibility and restraint.

A Concert of Powers reflects the reality of geopolitics: it will not eliminate geopolitical rivalry nor be a reconstituted UN. But it could offer a vital mechanism for channeling competition, discouraging unilateralism, and reinforcing regional stability worldwide. For the polycentric world of today, it may prove the most realistic path toward cultivating coexistence and minimizing the risk of internecine global wars involving nuclear states.

The Path Forward: Building a Concert for the 21st Century

The first step toward establishing a Concert of Powers is fostering a shared understanding among the world’s great and middle powers. This requires sustained high-level diplomatic engagement aimed at identifying common strategic interests and testing practical areas of cooperation. Existing platforms such as the G20 or BRICS+ could serve as preliminary venues for these conversations, but the long-term goal must be to create a separate forum grounded in geopolitical realism.

Second, the Concert will need a flexible but coherent framework for coordination. Unlike the informal consultations of 19th-century Europe, a modern Concert may benefit from some regularized structure — periodic leadership summits or ministerial meetings — without succumbing to institutional rigidity. A hybrid format, balancing structure with strategic agility, offers the best chance of success.

The Concert must be viewed not as a successor to liberal institutions, but as a corrective to their limitations — a geopolitical forum for great-power diplomacy in a more pluralistic and regionally anchored world.

Third, a credible mechanism for agenda-setting and issue prioritization is essential. This could involve a rotating chairmanship, allowing each major power to highlight specific concerns, or the creation of a small secretariat tasked with preparing discussion materials and proposing joint initiatives based on shared strategic interests. Such mechanisms would help prevent dominance by any one state while ensuring focus on issues of global consequence.

Fourth, and most critically, the Concert’s success depends on the willingness of its members to commit to a basic code of conduct: mutual restraint, non-interference, and collective crisis management. This represents a shift from a narrow-minded diplomacy to a holistic one rooted in a shared interest in stability. To preserve credibility, the Concert must have means — whether diplomatic pressure, reputational consequences, or suspension — to respond to violations of these norms.

America’s Role

As the leading architect of the post–World War II order and still the most globally capable power, the United States is uniquely positioned to initiate the conceptual and diplomatic groundwork for a 21st-century Concert. This will require a deliberate shift from hegemonic globalism toward strategic coordination among major powers.

Washington should begin by convening exploratory discussions with other major powers — particularly China, India, Brazil, Russia, France, Turkey, Iran, Germany, and Japan — to assess the feasibility of a more focused geopolitical dialogue. Rather than seeking universal rules or global norms, the U.S. should frame the Concert as a pragmatic mechanism for managing rivalries, preventing regional or global war, and coordinating on select issues of mutual concern.

In parallel, the United States should advocate for a lean, principles-based framework centered on peaceful dispute resolution, collective security, and reciprocal restraint. These foundational understandings would define the Concert’s strategic ethos, without attempting to remake the world in any one power’s image.

Crucially, the Concert must be viewed not as a successor to liberal institutions, but as a corrective to their limitations — a geopolitical forum for great-power diplomacy in a more pluralistic and regionally anchored world. Success will depend not on idealism, proceduralism, or institutional proliferation, but on a shared recognition that peace among major powers is the irreducible core of international stability.

Conclusion: A Concert for a More Stable and Secure World

The United States can help shape a post-unipolar world by promoting a 21st-century Concert of Powers — not as a vehicle for universal values or world government, but as a necessary framework for managing complexity, rivalry, and interdependence in an international system that is increasingly regional and pluralistic, as it was for much of history.

The obstacles are significant: deep mistrust, divergent worldviews, competing ideologies, and contested spheres of influence. Yet the rewards — a disciplined system of major-power coexistence, a mechanism for defusing escalation, and a way to constrain global hegemonic ambition without war — are even greater.

The Concert model is not utopian; it is adaptive, pluralistic, and rooted in realism. It accepts that consensus may be limited and that cooperation will be partial, but it insists that stability can emerge from dialogue, strategic empathy, and systematic engagement among the world’s principal powers.

In a shifting world that is returning to familiar patterns of regional power and civilizational variety while remaining deeply interlinked, such a framework offers not a return to the past but a viable path forward.